This is a reprint of my article,

Iraq, Contingency Contracting and the Defense Base Act

By Susie Dow, ePluribus Media, March 4, 2007

Introduction

Iraq contractor. Those two words evoke different reactions from different people. For the families of the contractors who have been injured, kidnapped or killed as a result of simply doing their jobs,there's a much more pressing concern than public opinion: insurance.

In early 2005, Susie Dow became aware that a civilian contractor, Kirk von Ackermann, was not covered by "insurance" when he disappeared in Iraq on October 9, 2003. She sought to find out why. The story that follows is based on research, interviews, correspondence, documents, emails, and phone calls over a two year time span.

The first part of this series traces how the lack of adequate insurance coverage impacted families already suffering the deaths or uncertainty surrounding the status of their family members serving in Iraq or Afghanistan as civilian contractors. Part II concentrates on why the appropriate Defense Base Act clauses that could have made a difference went "missing in action." Part III focuses on the lack of information, training and access to low cost coverage for contractors based overseas.

Susie Dow has followed the Missing Man story since February 27, 2005. Her first ePluribus Media story

One Missing, One Dead; An Iraq Contractor in the Fog of War, follows the tale of two American civilian contractors.

Part I - Insurance

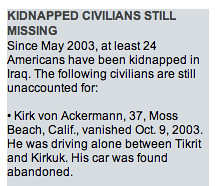

Kirk von Ackermann is missing.

So is his fellow worker, Ryan Manelick.

Although both men, contractors in the Iraq theater, have been declared dead, they are both missing from the official statistics of the injured or deceased maintained by the Department of Labor.

But let's back up a minute:

On March 18, 2003, one day before the start of the war in Iraq, Defense acquisition personnel were given a presentation that outlined recurring problems with insurance for contractors: contracts from the Department of Defense (DOD) were too often excluding Defense Base Act clauses, the very clauses that provided a modicum of insurance protection for civilian contractors. While both the State Department and the US Agency for International Development (USAID) secured low cost insurance for their overseas workers, the Pentagon consistently did not implement efforts for department-wide coverage. The rationale? To many, it seemed that for the DOD, saving money [1] was considered more important than broad access to coverage [2], coverage that would ensure surviving family members of kidnapped or killed contractors received compensation [3].

History of the Defense Base ActEstablished in 1941, the Defense Base Act (DBA) [4] provides the equivalent of workers' compensation for civilian contractors working on contingency operations in overseas countries such as Iraq and Afghanistan. DBA provides benefits in the event contractors are injured, killed, or kidnapped in the course of their work for US government agencies such as the various branches of the Department of Defense, USAID, or the State Department. But this insurance is not automatic, employers must purchase it. And before they can do that, they must know about it.

According to a January 23, 2007 USA Today and AP wire services story, the Department of Labor who administers DBA benefits, reports that at least 770 contractors have died [5] and 7,761 contractors have been injured in Iraq between March 2003 to December 31, 2006.

At least two American contractors should be listed: Ryan Manelick and Kirk von Ackermann. They are not, however, included in DBA casualty figures.

[

Editor's note: in October 2008, author Susie Dow learned that the Department of Labor did not release casualty information on companies with fewer than 7 incidents out of concern for privacy. However, the policy is not a legal requirement and as a result, its merit is questioned.]

The Slow Pace of BureaucracyDeirdre A. Lee, former Director of Defense Procurement and Acquisition, attended that March 18th, 2003 briefing [6] of the Defense Acquisition Excellence Council, highlighting that contracts with the Department of Defense did not always include the required DBA contract clauses.

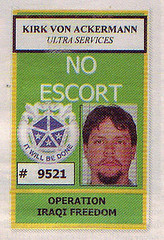

Seven months after that briefing, on October 9, 2003, civilian contractor Kirk von Ackermann working for Ultra Services of Istanbul, Turkey, which fulfilled logistics contracts for the US Army, disappeared in Iraq.

Nine months after that same briefing, on December 8, 2003, Director Lee belatedly issued a policy memo to [7] Defense agencies indicating that DBA was a required contract clause that should be included in overseas contracts where appropriate. Within one week, von Ackermann's colleague, Ryan Manelick, was gunned down after leaving a meeting at a base in Iraq.

Eighteen months after that briefing, the two Ultra Services principals would learn for the first time of the necessity of DBA insurance, too late to cover either of the two men. With no coverage, both men are omitted from the statistics the Department of Labor compiles on Iraq contractors.

The Family Left BehindWhen Kirk von Ackermann disappeared on that October day in 2003, he left behind a wife and three children.

Within a month of first learning about the Defense Base Act in March 2004, Megan von Ackermann filed a claim for compensation. To contact her husband's employer Ultra Services, which by that time had ceased operations, a claims examiner faxed a letter of inquiry dated August 5, 2004 ultimately reaching Ultra Services' principals John Dawkins and Geoff Nordloh. The inquiry requested information on von Ackermann's disappearance as well as the name and address of Ultra Services' Defense Base Act insurance carrier.

But, Ultra Services didn't have DBA insurance. In fact, the company principals had never even heard of DBA during the time of their work in Iraq despite the fact that Ultra Services had processed over $12 million in contracts.

And even though Nordloh and Dawkins had also fulfilled millions of dollars in contracts for the US Army in Afghanistan, they only had just first learned of the Defense Base Act requirement from another contractor, construction giant Perini, through a draft of a proposed subcontract for work with the US Army in Afghanistan in the summer of 2004. In none of Dawkins' or Nordloh's previous prime contracts had the US Army ever mentioned the need for DBA.

Meanwhile, Megan von Ackermann had another problem -- her husband was considered "missing," not dead. The Department of Labor initially indicated that they needed the US Army's Criminal Investigation Division's (CID) findings into her husband's disappearance before they could decide her claim's status.

On August 9, 2006 -- two years after the initial letter was faxed -- the CID informed Megan von Ackermann that they had determined that her husband, a former Air Force Captain, had been killed on October 9, 2003 during a botched kidnapping [8]. While CID's determination allows Megan to move forward with processing a claim, it doesn't resolve the issue that Ultra Services didn't have DBA insurance at the time of her husband's disappearance. To this date, his remains still have not been found.

The von Ackermann family is unlikely to ever collect DBA benefits. Worse, since Kirk von Ackermann was considered a missing person for almost three years, and as a result, his family was not eligible for Social Security survivors' benefits [9], until the determination by CID. For the von Ackermann family, meeting day-to-day expenses is an ongoing problem:

I worry about money constantly - and I hate it. I don't want to reduce our situation to finances, and in a way I'm afraid the stress over money is masking the pain of our loss. The two things are so huge... and that hurts too; it hurts that being poor is nearly as difficult as losing Kirk. -- Megan von Ackermann [10]

Unfortunately, the von Ackermann family's experience is not unique. An Associated Press article reported Lillian Ake, wife of missing Iraq contractor Jeffrey Ake, is also unable to collect benefits. While she and her four children have received financial support through her church, Lillian Ake has placed their family home on the market in addition to beginning bankruptcy proceedings for her husband's business. [11] Jeffrey Ake was last seen being held at gunpoint in an April 13, 2005 video.

Contingency ContractingLike Jeffrey Ake, Kirk von Ackerman and Ryan Manelick were civilian contractors working in a "contingency operation." As designated by the Secretary of Defense, Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF) in Afghanistan [12] and Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF) in Iraq [13] are both contingency operations. [14] As such, the procurement of goods and services in support of these operations is known as Contingency Contracting and is performed by Contingency Contracting Officers (CCOs). [15]

Contingency contracting, by its very nature of working in close proximity to the battlefield, brings high risks. Civilian contractors deliver much needed supplies and services and, in doing so, often find themselves situated closer and closer to hostilities as competitive outsourcing through the US government's A-76 [16] program increasingly determines the most cost-effective way to fulfill government operations is through the private sector.

ContractorsBased on a survey for CENTCOM [17], and as reported in a December 5th, 2006 Washington Post article, more than 100,000 American and Third Country National civilian contractors [18] are estimated to currently be working in Iraq. Notably, this number does not include their sub-contractors. Requiring DBA insurance coverage depends in part on the "type" of support a civilian contractor provides.

Three types of civilian contractors are on or near the battlefield supporting contingency operations:

Systems support contractors maintain specialized equipment, generally sophisticated weapons. [19]

Theater support contractors are contracted by contingency contracting officers to provide immediate goods and services, generally by local vendors.

External support contractors, perform logistical support such as base construction and maintenance.

Ultra Services, the company Von Ackerman and Manelick worked for, was an external support contractor, similar to the more well-known, although much larger, Halliburton subsidiary Kellogg, Brown and Root (KBR). In fact, as external support contractors, ------------. KBR administers the Logistics Civil Augmentation Program (LOGCAP) III contract for the US Army.

According to one former US Military contracting officer, as a result of LOGCAP, KBR has its own contracting officers who procure goods and services for the Department of Defense's contingency operations. KBR employees are required to be covered by DBA insurance and, per the terms of the LOGCAP contract, KBR also requires that their subcontractors be adequately covered by DBA insurance as well. [20]

Had everything gone according to the Pentagon's plans, Halliburton's KBR unit would have handled most of the contracts for logistics in Iraq. [21] Companies such as Ultra Services would have served as subcontractors to KBR so that, by default, their employees would have been covered by DBA insurance coverage. Unfortunately for the von Ackermann family, the Pentagon's assumptions met a different reality.

Who Cares?The Department of Defense was obligated to have all of its contractors who are legally required to carry DBA insurance to do so. Unfortunately, the Department of Defense's implementation was less aggressive than other US governmental agencies.

Whereas the State Department and USAID had for many years secured reasonable rates from insurance carriers for DBA, rates that added less than 5% to contract costs, the Department of the Defense did not. For other agencies, rates remained low as underwriters spread risks, charging the same rates in safer countries. But for years, the Department of Defense resisted efforts to secure broad coverage for its contractors. By the time the Department of Defense solicited competitive bids, its efforts met failure:

"On August 8, 2003 after the invasion, the Defense Department asked insurance agencies to submit proposals for selling discounted death and injury coverage to military contractors in Iraq, Afghanistan and Kuwait.

Not a single insurance company bid on the solicitation, which expired September 2, 2003 because the risks were too high to make it profitable." [22]

At the same time that the Department of Defense was failing to secure DBA insurance for its contractors at a reasonable cost, Operation Enduring Freedom was nearing the end of its second year in Afghanistan; Operation Iraqi Freedom, was nearing the end of its first six months. Meanwhile, DBA insurance rates for Department of Defense contractors – not surprisingly -- had skyrocketed well above those of USAID and State Department contractors, in some cases almost doubling overall contract costs. [23]

Eventually, the Department of Defense would later learn it was paying out as much as 10 times more in premiums than the other two government agencies [24]. The US taxpayer, of course, picked up the tab. [25]

Part II: DBA Clauses Missing In Action

The first part of this series traced how the lack of adequate insurance coverage impacted families already suffering the deaths or uncertainty surrounding the status of their family members serving in Iraq or Afghanistan as civilian contractors. Part II concentrates on how the appropriate Defense Base Act contract clauses that could have made a difference went "missing in action."Missing in Action

For those writing and administering contracts, whether or not to include the appropriate Defense Base Act (DBA) clauses requiring insurance protection for civilian contractors is left to individual contracting officers. At best when the appropriate clauses are missing, the contract was mistakenly assumed to be exempt. At worst, the clause was overlooked or never considered.

Gray Zone

Department of Defense contracts are generally divided into three types: services, supplies, and construction.

Both "services" and "construction" contracts require DBA clauses. But civilian contractors who provide "supplies" on or near the battlefield are generally exempt from carrying DBA insurance. However, in some instances, contractors who provide supplies where the contract requires work on site -- known as "service incidental to supply" -- are not exempt.

1Current language within Federal Acquisition Regulation (FAR)

2 is ambiguous and may appear to waive the requirement of DBA coverage by creating grey zones for service incidental to supply. These grey zones leave each contingency contracting officer to interpret FAR to the best of his or her ability and to determine when and where they should include DBA clauses.

The Defense Base Act clause is a mandatory clause that must be included in appropriately designated contracts awarded by any federal agency for overseas performance. It should be included in the "check list " provided to government contracting officers with responsibility for soliciting and awarding contingency (and any other) type of contracts for overseas performance. -- Alan Chvotkin of the Professional Services Council 3

One can argue that the work of Ultra Services and its employees, Kirk von Ackermann and Ryan Manelick, may have fallen outside of "service incidental to supply." That is, the contracts they worked under were exempt from DBA because they supplied US forces with prefabricated Containerized Housing Units (CHUs) and their work was not sufficient to warrant DBA coverage.

Although purchases of trailers such as Containerized Housing Units (CHUs) are handled by supply contracts and are usually exempt from DBA, CHUs require some supervision from the contracted vendor -- in this case, Ultra Services -- on the work site itself such as offloading from shipping trucks, placement on concrete pads, and hook-up of utility lines.

Given such activity at the worksite, should the supply contracts for the purchase of CHUs include DBA clauses? Contingency contracting officers were left to figure it out on their own. Complicating the matter, while deployed in a war zone, contingency contracting officers also had other priorities.

In 2003, during the time von Ackerman and Manelick were in Iraq, contingency contracting officers (CCOs) were expected to respond rapidly to the priorities set by their commanders for fulfilling the immediate needs of 173,000 troops. They were also expected to verify that, where needed, subcontractors also had DBA in place.

With upwards of 200 requisitions and 400 contracts on the CCOs' desks, each CCO had to decide between 1) carefully including all relevant contract clauses and verifying each contractor's insurance paperwork -- which could add delays or 2) quickly expediting the contracts to secure the needed supplies and services for troops.

A 21st-century military force "burns up" a tremendous volume of expendable supplies and continuously needs repairs to equipment as well as medical treatment. Without a plentiful and dependable source of fuel, food, and ammunition, a military force falters. First it stops moving, then it begins to starve, and eventually it becomes unable to resist the enemy.

4 -- Patrick Lang, Christian Science Monitor.

Under such a pressure, it should come as no surprise that some supply contracts were little more than a statement of understanding, with an actual contract following months later. The Department of Defense placed its contingency contracting officers in an untenable position. Either the troops on the ground suffered shortages or the civilian contractors and their families faced the risk of being uninsured in a dangerous environment. Even today, unless more detailed language is added to the Federal Acquisition Regulation (FAR), contingency contracting officers are likely to be unaware of decisions that clarify policy

5 -- most especially while deployed in war zones -- as they prioritize fulfilling troops' needs over paperwork.

Bandaid or Surgery?The sheer volume of work, compounded by a lack of clear guidance from the Department of Defense promoted confusion. Confusion, the Department of Defense should have both expected and been prepared for.

And indeed, the Special Inspector General of Iraq Reconstruction (SIGIR) issued a report, Iraq Reconstruction:

Lessons Learned in Contracting and Procurement which analyzed contracting problems and made several recommendations. One recommendation was to establish a new Contingency FAR specifically for contingency operations. Another prompted the Deputy Secretary of the Army for Policy and Procurement to prepare two new guidebooks:

The Army Guidebook for OCONUS Contingency Contracting and

CONUS Guide for Supporting Emergencies within the United States and Supporting Overseas Contingencies from CONUS Locations.

Drafts of the guidebooks reportedly rely on Special Operations Command (SOCOM) contracting documents as well as on the

Air Force Guidebook on Contingency Contracting6 a source that a review showed

7contained no reference to DBA insurance.

In September 2003, the US Army issued a new guidebook,

Army Contractors Accompanying the Force (CAF) 8 which included two pages on the necessity of Defense Base Act coverage. Acquisition personnel knew contractors may not be aware of the DBA, as pointed out within the guidebook:

Pursuing benefits and remedies under these laws is the responsibility of the contractor employee and/or contractor. Since they may be unaware of this assistance, however, contracting personnel should inform the contractor of these laws if the situation arises. 9

The contractor is ultimately responsible.

Insurance in some circumstances is available under the Defense Base Act and Longshoreman's and Harbor Workers Compensation Act administered by the Department of Labor, and the War Hazards Act. It is the contractor's or employee's responsibility to pursue possible benefits under those Acts.

10Yet, for the families of civilian contractors, it is imperative that both new guidebooks include clear guidance on the implementation of the Defense Base Act for the tens of thousands of civilian contractors working overseas.

Ducking ResponsibilityThe SIGIR report, Lessons Learned, confirmed that by Spring 2003 the Department of Defense had fully expected the Logistics Civil Augmentation Program (LOGCAP III), as administered by Halliburton's KBR, to reliably fulfill ALL logistics needs in Iraq.

11 Had KBR done as the Pentagon expected, companies such as Ultra Services would have clearly understood they were required to carry DBA insurance for their employees. Had Ultra Services secured coverage, Kirk von Ackermann's family would have received benefits during the entire duration he was considered missing, sparing his family the added burden of financial hardship.

But unfortunately, due to the urgency and sheer volume of needs required by deploying 173,000

12 troops to the Iraq region, many of the responsibilities expected to be coordinated by KBR actually fell to Department of Defense contracting officers. Simply put: the Department of Defense had grossly underestimated and severely misjudged the abilities of LOGCAP III to handle Iraq contracts and by extension, insurance protection for its contractors. The Pentagon was unprepared to handle logistics on the battlefield.

As succinctly pointed out by Dov S. Zakheim, the Pentagon's comptroller from 2001 until 2004, "You're really asking too much of one firm to be able to manage all of this."

13 As further proof of this basic fact -- that no one company could provide 100,000 contractors -- the Department of Defense announced in July 2006 that the next contract for logistics support, LOGCAP IV, would be split and awarded to three separate external support contractors.

14 And a fourth contractor will "monitor the performance" of the other three.

Finding Insurance On The BattlefieldWhile the Department of Defense in Washington DC expected external support contractor KBR to fulfill LOGCAP III, life in theater didn't cooperate. Contingency contracting officers were confronted with the necessity of working with local contractors to get urgently needed requisitions filled. Waiting for KBR to deploy sufficient staff and personnel to implement LOGCAP III throughout Iraq was not a viable option. Additionally, the expectation that contractors already operating in Iraq would have secured some form of local workers' compensation coverage was unrealistic.

Even if they'd known of the need for DBA insurance, local companies such as Ultra Services had few options. Iraq didn't have much in the way of a robust private insurance industry. Many Iraqis had relied on government insurance programs. Reporting on an early briefing held by Bechtel for local Iraqi companies in Baghdad, July 2003, Kelly Hayes-Raitt wrote:

Before this last war, there were six insurance companies in Iraq, the largest of which were run by Saddam Hussein's government. They offered basic auto and casualty insurance, workers compensation and liability insurance with maximum policies of either 200 million or 150 million dinars (about $100,000 or $60,000, respectively). As of July [2003], only one insurance company was operating. The others had been shut down or looted. 15

As one example of these difficulties, when local Iraqi companies first sought work as Bechtel subcontractors, they were told to get insurance.

16 But there was no mechanism in place to procure the three types of insurance Bechtel required -- indemnification, bid security, and performance, so eventually, Bechtel told their potential subcontractors that American companies would provide it. Finally, even unable to make that solution work, Bechtel waived their insurance requirements for Iraqi sub-contractors altogether

17. Under LOGCAP III, today, KBR does not normally require liability insurance

18 from its Iraq sub-contractors, but instead requires DBA coverage which is easier to obtain through a referral to its own insurance carrier, AIG.

19Civilian Contractors Assuming Military Risks

Why is the insurance situation for civilian contractors important?

Since 2000, the number of contract obligations and contract actions by the Department of Defense has nearly doubled.

20 As more services within the military are privatized or outsourced,

21 reliance on civilian contractors supporting overseas contingency operations increases -- civilian contractors assume risks once handled entirely by military personnel.

The administration's own numbers illustrate how dramatically the warrior is becoming privatized.

With their increased presence, more civilian contractors, such as Ultra Services' von Ackermann and Manelick, face the possibility of injury, kidnapping and death. Accordingly, the Department of Defense and the Department of Labor have a responsibility to ensure broad implementation and uniform dissemination of DBA contract clauses.

Part III: Information, Training & Access

Part I of this series traces how the lack of adequate insurance coverage impacted families already suffering the deaths or uncertainty surrounding the status of their family members serving in Iraq or Afghanistan as civilian contractors.

Part II concentrates on why the appropriate Defense Base Act (DBA) clauses that could have made a difference went "missing in action."

Part III focuses on the Defense Department's (unlike its counterparts in the State Department and United States Agency for International Development (USAID)) inability to provide information, training and access to low cost coverage.

What Went Wrong?Inadequate planning, staffing and implementation seem to be the main culprits in the Department of Defense's inability to implement Defense Base Act procedures, especially in light of the other government agencies' ongoing success in doing so.

Stepping back five years to see what happened to the Department of Defense's efforts, we start in March of 2002, when two former councils1 combined to create the Defense Acquisition Excellence Council (DAEC). The DAEC was established to:

...address acquisition, technology and logistics issues that cut across organizational and functional boundaries [and] to collectively work issues as well as take actions to accelerate implementation of the Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition, Technology & Logistics (AT&T) initiatives to achieve acquisition excellence. 2

One of the earliest meetings of the new DAEC, 3 March 18, 2003 mentioned in Part I of this series was the same briefing that Deirdre A. Lee, then Director of Defense Procurement and Acquisition, attended but failed to act upon for over 9 months.

The presenter that day who outlined the difficulties with DBA was Alan Chvotkin of the Professional Services Council (PSC). PSC is "the leading national trade association representing the professional and technical services industry doing business with the Federal government"4 In his briefing, Chvotkin showed the slide on the left.

Alan Chvotkin's slide was clear. His action list provided immediate steps to solve the DBA problem. And those immediate steps weren't merely hypothetical -- Chvotkin based his presentation in part on an informal telephone survey he conducted with PSC member companies that had contracts from the Department of Defense.5 A number of those member companies' contracts had not included DBA clauses even though they should have been required to.

Like so many other government contracting matters, overseas contracting requires specialized training and experience. [...] We found that, during the initial phases of the Iraq conflict, the responsibility for contracting was more highly diffused among DoD contracting officers, some of whom did not traditionally award overseas contracts. That lack of familiarity, coupled with the urgency of some awards and the ambiguity of the scope of coverage of the DBA clause, probably contributed to the failures to include this specific provision in all contracts.6 -- Alan Chvotkin

Although it took 9 months to be issued, Director Deirdre A. Lee's memo clearly recognized the severity of the problem that Chvotkin had so succinctly outlined.

Subject: Inclusion of Defense Base Act Clause in DOD Overseas Contracts

It has come to my attention that there may be some inconsistency within the Department regarding the inclusion of the Workers' Compensation Insurance (Defense Base Act) clause at FAR 52.228-3 in our contracts to be performed outside of the United States. [...]

I want to emphasize that the Workers' Compensation Insurance (Defense Base Act) clause FAR 52.228-3 should be included in all DoD service contracts to be performed (either entirely or in part) outside of the United States, as well as in all supply contracts that also require the performance of employee services overseas. [sic]

Despite the strong wording of Director Lee's memo, there were (and continue to be) few opportunities for contingency contracting officers to learn how to determine where, how, and for whom to include the appropriate DBA clauses.

As just one example, as recently as November 2006, a contractor had to point out to its military contracting officer that DBA was required and should be included as a cost in a service contract proposal for the US Army. In response, the contracting officer replied -- in writing -- that having spoken with "legal," DBA was "not required." Yet, the contract was for trucking, a service that is known, even to the general public, as carrying a high risk of injury in its region of operations. [7]

Training for DBA requirements: A Well-Kept SecretPrior to December 2003, contractors and subcontractors hoping to learn about DBA and its application to Department of Defense contracts would find little information. In 2001, two years prior to Director Lee's attendance of the meeting, the Department of Labor (DOL), which administers Defense Base Act claims, had growing concerns of employers not carrying DBA. [8] To rectify the situation, the DOL's Office of Workers' Compensation Programs (OWCP)'s initiated seminars domestically [9] "to inform employers about the obligation to insure their workers and about the severe costs for not doing so." Since this was before the Iraq and Afghanistan conflicts, at that time, there was no mention of seminars for overseas contractors. The OWCP was most concerned about employers, predominately in Florida, with maritime workers as their employees.

Web pages from the Department of Labor were light on DBA information.10 On the Defense Base Act (DBA) Information page, [11] there was one link to the DLHWC (Longshore) homepage for more detail on "periodic seminars and workshops for industry groups."

Defense Base Act Seminars and WorkshopsThe OWCP National Office and district offices hold periodic seminars and workshops for industry groups as the need arises, or upon request. For information on upcoming events, check the official Longshore website.

Indeed, the first known DBA workshop would not be announced until November 14, 2003 [12] and scheduled for December 15, 2003, the day after Ultra Services civilian contractor Ryan Manelick was killed in Iraq. The announcement read:

Due to overwhelming demand, the Department of Labor, Office of Workers' Compensation Programs, will conduct a one day workshop on the Defense Base Act and the War Hazards Compensation Act. The date of the workshop is Monday, December 15, 2003. [13]

Unfortunately, there appeared to be no such seminars or workshops scheduled for contractors in Afghanistan and Iraq. Unless they were in the United States, overseas contractors who didn't know to secure DBA insurance or its equivalent, they wouldn't learn about it through Department of Labor seminars and workshops.

And, if the civilian contractors working in Iraq looked to the Coalition Provisional Authority (CPA) for information and training on DBA, they certainly wouldn't find much help. Of four documents available online through the CPA, two were dated June 11, 2004 -- 17 days before the CPA handed over sovereignty to the Iraqi people. Of the remaining two, the most extensive, from insurance company Rutherfoord, had a creation date of November 20, 2003 -- eight months after Coalition forces had moved into the region. [14] The last and earliest of the four, from American International Group Inc (AIG), with a May 16, 2003 creation date, contained only the following on DBA:

Defense Base Act (DBA) - AIG's member companies have been in the business of writing coverage in response to the DBA for many years. The Act was passed during World War II to provide compensation for disability or death to personnel employed at American military, air and naval bases outside the United States. The Act has evolved to cover contracts and subcontracts approved and financed by any independent establishment or agency of the United States ... Upon adequate lifting of sanctions, we plan to have employees on the ground in Iraq. [15]

Obviously, overseas contractors weren't going to learn about DBA from the CPA.

In September 2003, the US Army issued a new guidebook, Army Contractors Accompanying the Force (CAF). [16] which included two pages on the necessity of Defense Base Act coverage. Acquisition personnel knew contractors may not be aware of the DBA, as pointed out within the guidebook:

Pursuing benefits and remedies under these laws is the responsibility of the contractor employee and/or contractor. Since they may be unaware of this assistance, however, contracting personnel should inform the contractor of these laws if the situation arises. [17]

The contractor is ultimately responsible.

Insurance in some circumstances is available under the Defense Base Act and Longshoreman's and Harbor Workers Compensation Act administered by the Department of Labor, and the War Hazards Act. It is the contractor's or employee's responsibility to pursue possible benefits under those Acts. [18]

Eventually, in 2005, two years after the start of the Iraq war, the Defense Contract Management Agency at dcma.mil, which provides Contingency Contract Administration Services,19 published an article by Michael Dudley, Contractors on the Battlefield: Part III20 that summarized Chvotkin's 2003 PowerPoint presentation.

Congress Jumps InThroughout the Iraq war, there continues to be problems with DBA implementation. Over 100 members of Congress requested reviews related to Iraq and DBA, and finally, in April 2005, the Government Accountability Office (GAO) reported that a review of costs and implementation was needed:

Defense Base Act Insurance: Review Needed of Cost and Implementation Issues [21]

This report explains DBA requirements; discusses DBA insurance rates, which are higher for DOD than for other agencies; identifies challenges and concerns that federal agencies face when implementing DBA; and suggests that Congress consider requiring that the Director of the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) determine, in coordination with DOD, the Departments of Labor and State, and the U.S. Agency for International Development, what actions should be taken to address issues that came to light during our review.

In response, the Department of Defense (DOD) provided details of a new 1-year pilot program for DBA insurance for the US Army Corps of Engineers, a decision based soley on the escalating costs rather than on protection for contractors who are working in the war theatre, even as the Department of Defense continued to replace its military personnel with private sector civilians.

DOD completed a congressionally directed study in 1996 on the feasibility and desirability of initiating a single-insurer program. While DOD concluded at that time that such a program would not lead to cost savings, the DBA insurance rates defense contractors are now paying have led to concerns among DOD officials over the cost of DBA insurance. To address these concerns, DOD, through the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, issued a solicitation on March 7, 2005, for a 1-year pilot contract to a single insurer for DBA insurance for all Army Corps of Engineers contractors performing work overseas. [22]

On December 1, 2005, the Department of Defense's U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) finally awarded CNA Financial Group the contract for the new Defense Base Act (DBA) pilot program. [23] As of December 2006, almost 4 years of war in the mid-east and, although during the same time period the USAID and State Department had had effective DBA coverage for its contractors, the Department of Defense has only just finished its pilot program.

If successful, the program could revolutionize consistent DBA implementation throughout the Armed Services for civilian contractors working overseas. For the eligible, but uninsured contractors who were kidnapped, injured or killed, the revolution comes much too late.

Contractors at RiskFour years. Two wars. Two countries. Two contingency operations. Hundreds of billions of dollars in contracts. Tens of thousands of civilian contractors. Thousands of injuries. Hundreds of deaths.

Why was the Department of Defense so inept implementing the Defense Base Act --placing contractors, and their families, at risk? The Government Accountability Office's June 2006 report Contract Management: DOD Vulnerabilities to Contracting Fraud, Waste, and Abuse, [24] may reveal the answer:

DOD's tone at the top allows a certain level of vulnerability to enter into the acquisition process. Senior acquisition officials ultimately shape the environment that midlevel and frontline acquisition personnel operate within, and it is that tone that clearly identifies and emphasizes the values deemed acceptable within the acquisition function. [...] DOD officials told us that, in recent years, the tone set in DOD was one of streamlining acquisitions to get results as fast as possible. While this is a desired outcome of the acquisition process, the acquisitions should still be carried out within prescribed policies and practices.

As the Deputy Secretary of the Army for Policy and Procurement prepares two new guidebooks for contingency contracting:

The Army Guidebook for OCONUS Contingency Contracting and

CONUS Guide for Supporting Emergencies within the United States and Supporting Overseas Contingencies from CONUS Locations, it is imperative that both include clear guidance on the implementation of the Defense Base Act.

For the families of contractors such as Kirk von Ackermann and Ryan Manelick the Manuals come much too late.

ePluribus Media Contributors: rba, newton snookers, cho, intranets, steven reich, wanderindiana, standingup, roxySide Bars Part I & II

Defense Base Act

The Defense Base Act provides disability compensation, medical treatment, and vocational rehabilitation to workers injured at work and death benefits to survivors when the worker is killed on the job. You need not be a U.S. citizen or a U.S. resident to obtain these benefits. [SB1] Source: Department of Labor

Contingency Operations

A military operation that is designated by the Secretary of Defense as an operation in which members of the armed forces are or may become involved in military actions, operations, or hostilities against an enemy of the United States or against an opposing militaryforce; or results in the call or order to, or retention on, active duty of members of the uniformed services [...] or any other provision of law during a war or during a national emergency declared by the President or Congress. [SB2] Source: US Code

Contingency Contracting

Contingency contracting is direct contracting support to tactical and operational forces engaged in the full spectrum of armed conflict and military operations (both domestic and overseas), including war, other military operations, and disaster or emergency relief. [SB3] Source: US Army Standard Procurement System

Federal Aquisition Regulation

FAR 28.305 [SB4] Overseas workers' compensation and war-hazard insurance.

FAR 28.310 [SB5] Contract clause for work on a Government installation.

For more information on FARS, please see the endnote section.

References

Please email me if you need assistance locating original source material cited in the references.Endnotes - Part I1 http://www.gao.gov/htext/d05280r.html -- see notes on 1996 review, “DOD concluded at that time that such a program would not lead to cost savings

2 http://www.gao.gov/htext/d05280r.html; The title of one section is “Large Numbers of Contractors in Iraq Have Led to Concerns over the Cost of DBA Insurance”

3 Ibid.

http://www.gao.gov/htext/d05280r.html4 FAR 52.228-3 Workers Compensation Insurance (Defense Base Act)

5 Americans die in security contractor copter crash,

USA Today, USA Today Staff and Wire Reports, AP, January 23, 2007

According to a Guardian article,

http://www.guardian.co.uk/worldlatest/story/0,,-6436602,00.html, The AP had to file a Freedom of Information Act request to obtain figures on pre-2006 civilian deaths and injuries from the Labor Department.

9 Email correspondence with Megan von Ackermann

10 Email from Megan von Ackermann to Susie Dow Auguest 22, 2006 5:55 AM

11 Fund to help wife of Iraq kidnap victim by AP, January 12, 2007

12 Authorization to Utilize Contingency Operations Contracting Procedures, THE UNDER SECRETARY OF DEFENSE, E.C. Aldridge, Jr., October 9, 2001

13 MEMORANDUM FOR ALMAJCOM/FOA/DRU (CONTRACTING), Emergency Acquisitions in Direct Support of U.S. or Allied Forces Deployed in Military Contingency Operations during Operation Iraqi Freedom, CHARLIE E. WILLIAMS, JR., March 21, 2003

14 FAR 2.101 Definitions: "Contingency operation" (10 U.S.C. 101(a)(13)) means a military operation that: (1) Is designated by the Secretary of Defense as an operation in which members of the armed forces are or may become involved in military actions, operations, or hostilities against an enemy of the United States or against an opposing military force; or (2) Results in the call or order to, or retention on, active duty of members of the uniformed services under section 688, 12301(a), 12302, 12304, 12305, or 12406 of 10 U.S.C., Chapter 15 of 10 U.S.C, or any other provision of law during a war or during a national emergency declared by the President or Congress.

15 For the purposes of this article, contingency operations and contingency contracting refer to support of overseas US government agency missions on or near the battlefield as managed by the Pentagon.

16 Circular No. A-76 Performance of Commercial Activities, August 4, 1983, Revised 1999 & the Government shall not start or carry on any activity to provide a commercial product or service if the product or service can be

procured more economically from a commercial source.

17 White House Office of Budget and Management, Robert A. Burton, Memorandum:

Request Contracting Information on Contractors Operating in Iraq, May 16, 2006

18 Renae Merle,

Census Counts 100,000 Contractors in Iraq Civilian Number, Duties Are Issues, Washington Post, Tuesday, December 5, 2006; Page D01

19 Is Force Protection For Contractor Personnel on the Battlefield Adequate? by Mr. Michael J. Dudley, DCMA, Spring Summer 2004 (I have reason to believe this article was intended to be published earlier – note footnote dates: May 2003)

20 Interview and follow up emails with Former US military contracting officer.

21 Iraq Reconstruction:

Lessons Learned in Contracting and Procurement, Special Inspector General of Iraq Reconstruction, July 2006, p 14

22 Bechtel Benefits as Iraq Contractors Struggle to Get Insurance Bloomberg News, November 21, 2003

Iraq contractors' sky-high insurance costs hobble efforts (reprint of same article, slight variation) by Vernon Silver, Bloomberg News, November 27, 2003

23 IRAQ: Army and Insurer at Odds, by T. Christian Miller, The Los Angeles Times, June 13th, 2005

24 US:

Defense Discovers Insurance Companies Charge Huge Fees for Contractors Overseas, by Elliot Blair Smith, USA Today, June 14th, 2005

25 Iraq contracts burden taxpayers, By Joseph Neff, McClatchy Newspapers, December 25, 2006

Sidebar ISB1 U.S. Department of Labor, Working for U.S. Government Contractors Overseas,

WHAT YOU SHOULD KNOW BEFORE YOU ARE INJUREDSB2 10 U.S. Code 101(a)(13)SB3 Standard Procurement System, SPS & Contingency ContractingEndnotes - Part II1 The Department of Labor Benefits Review Board had previously determined in 1988 in Alan-Howard v. Todd Logistics, Inc., 21 BRBS 70, that "individuals who work on-site to facilitate the utilization of such goods "constituted a service and as a result employees of such supply contractors were covered by DBA.

3 email from Alan Chvotkin to Susie Dow Friday, July 07, 2006 5:11 PM

4 The vulnerable line of supply to US troops in Iraq By Patrick Lang, Christian Science Monitor, July 21, 2006

5 ARMY CONTRACTORS ACCOMPANYING THE FORCE(CAF), Guidebook, September 8, 2003 page 17 & 18 include information on DBA

6 Iraq Reconstruction:

Lessons Learned in Contracting and Procurement, Special Inspector General of Iraq Reconstruction, July 2006, pp 112-113 Also

see...7 Army Federal Acquisition Regulation (AFARS) Manual No. 2 for Contingency Contracting released November 1997

Air Force Federal Acquisition Regulation Supplement (AFFARS)

APPENDIX CC Contingency Operational Contracting Support Program (COCSP), revised June 15, 2006,

Navy Contingency Contracting Handbook

Marine Corps Purchasing Procedures Manual Appendix B8 ARMY CONTRACTORS ACCOMPANYING THE FORCE(CAF), Guidebook, September 8, 2003 page 18

9 ARMY CONTRACTORS ACCOMPANYING THE FORCE(CAF), Guidebook, September 8, 2003 page 17 & 18 include information on DBA

10 ARMY CONTRACTORS ACCOMPANYING THE FORCE(CAF), Guidebook, September 8, 2003 page 17 & 18 include information on DBA

11 Iraq Reconstruction:

Lessons Learned in Contracting and Procurement, Special Inspector General of Iraq Reconstruction, July 2006, p 14

12 Total US and Coalition Troops in May 2003,

The Iraq Index (PDF), May 30, 2006

13 Army to End Expansive, Exclusive Halliburton Deal, By Griff Witte, Washington Post, July 12, 2006

14 Army to End Expansive, Exclusive Halliburton Deal, By Griff Witte, Washington Post, July 12, 2006

15 Evidence Of Waste Of US Taxpayers' Dollars In Iraq Contracts Letter from Rep. Henry Waxman to Joshua Bolten, September 26, 2003

16 America's rebuilding of Iraq shuts out Iraqis by Kelly Hayes-Raitt, Santa Monica Daily Press, August 19, 2003

17 Bechtel's Outreach to Iraqi Subcontractors18In a few instances, contractors from surrounding nations are able to obtain liability insurance. But more often, KBR requires DBA coverage.

19 Former US military contracting officer

20 Contract Management:

DOD Vulnerabilities to Contracting Fraud, Waste, and Abuse, GAO-06-838R, p 8, Government Accountability Office, July 7, 2006

21Contract Management:

DOD Vulnerabilities to Contracting Fraud, Waste, and Abuse, GAO-06-838R, Government Accountability Office, July 7, 2006, http://www.gao.gov/new.items/d06838r.pdf

Sidebar IISB4 FAR 28.305SB5 FAR 28.310 (2) (a)Endnotes - Part III1 Single Process Initiative (SPI) Executive Council and the Defense Systems Affordability Council

2 DAEC charter letter, March 14, 2002

3 Contractors on the Battlefield: Part III by Mr. Michael J. Dudley, U.S. Army Defense Leadership and Management Program Participant Fall 2004/Winter 2005 - page 3

4 A-76 Revisions, Testimony to US House of Representatives, Committee on Government Reform, by Stan Soloway, June 26, 2003, page 2 See menu: Policy Leadership > Outsourcing/A-76 > Testimony > A-76 Revisions -- 6/2003 (actual link to pdf not available)

5 email from Alan Chvotkin to Susie Dow Friday, July 07, 2006 5:11 PM

6 email from Alan Chvotkin to Susie Dow Friday, July 07, 2006 5:11 PM

7 email to Susie Dow -- source prefers to remain anonymous

8 as documented in the DOL's Office of Workers' Compensation Programs (OWCP)'s annual report.

9Office of Workers' Compensation Programs (OWCP),

Annual Report to Congress FY 2001, page 28

10Internet Archive11 Ibid Link shown to

workshops and seminars12 Ibid

Announcement13 Division of Longshore and Harbor Workers' Compensation14 Rutherfoord The Assurance Company15AIG Solutions for Iraq Reconstruction16 ARMY CONTRACTORS ACCOMPANYING THE FORCE (CAF), Guidebook, September 8, 2003 page 18 -- ARMY CONTRACTORS

17 ACCOMPANYING THE FORCE (CAF), Guidebook, September 8, 2003 page 17 & 18 include information on DBA

18 ARMY CONTRACTORS ACCOMPANYING THE FORCE (CAF), Guidebook, September 8, 2003 page 17 & 18 include information on DBA

19 Contingency Contract Administration Services20 Contractors on the Battlefield:Part III by Mr. Michael J. Dudley, DCMA Communicator, Fall 2004/Winter 2005

21United States Government Accountability Office Defense Base Act Insurance:

Review Needed of Cost and Implementation Issues April 29, 2005

22 http://www.gao.gov/htext/d05280r.html

23 US Army Corps of Engineers Contracts with CNA for Defense Base Act Program, Global Risk Alert, AON, December 13, 2005

24 Contract Management:

DOD Vulnerabilities to Contracting Fraud, Waste, and Abuse, GAO-06-838R, pp 6-7 Government Accountability Office, July 7, 2006

Map inset showing the general location of Pacesetter originally published in the New York Times on December 29, 2003.

Map inset showing the general location of Pacesetter originally published in the New York Times on December 29, 2003. It's not clear which direction von Ackermann travelled after he left FOB Pacesetter.

It's not clear which direction von Ackermann travelled after he left FOB Pacesetter.